Aesop's Fables and How We Learn

What the stories reveal, especially in their modern form

I love Aesop’s Fables. I know I learned some of them as a small child, though I don’t remember that well, only that some were recognizable to me later. I love them, and I know them better know, because during the pandemic, my son and I would read them to each other each morning over our cups of coffee. That’s when we discovered something interesting.

Aesops’s Fables, will always come with these neat little morals added to the end of them (sometimes, they are even embedded into the fable, as something one of the characters says to another). These morals were, in fact, added to the stories. Aesop, so far as we can tell, did not include them in his own writing of the fables.

Each morning, my son would read a fable to me (without including the moral), and I would read a fable to him (without including the moral). The next day, we would look to see what the morals were for the previous day, then we would read the next two fables, without the morals.

After a short while, I noticed that many days, I would be thinking about the fable throughout the day, wondering what the moral was. Much to my surprise, I would start making my own morals for the story, and I found that sometimes my moral was better than the one in the book, sometimes it was the same, and sometimes (rarely, to be honest) it was was less insightful. Shortly thereafter, I started reading the fables to a group of young children (6-8 year olds) during an online meeting (remember, this was during the pandemic, so we would have homeschool meetings with young children). I would read the fable at the beginning of the meeting and ask them what they thought the moral was, because I wasn’t going to tell them. The 6-8 year olds were better at expressing morals for the fables!

I don’t know that I needed to ask them that question. I think I did it more to see what they would say. The reality is, the best thing about Aesop’s Fables is that they give us pictures (in words) of what the best virtues and the worst vices look like. The stories make me want to be like the courageous dog or the clever fox, and they make me not want to be like the proud peacock or the gluttonous dog. I don’t even have to name the virtue or vice to want to be like the animal (or not be like the animal, as the case may be).

The simple beauty of the story teaches me the lesson I need to learn. The moral, as it turns out, distracts me from that lesson. It makes me think I am supposed to be able to say those words, rather than like or not like the characters.

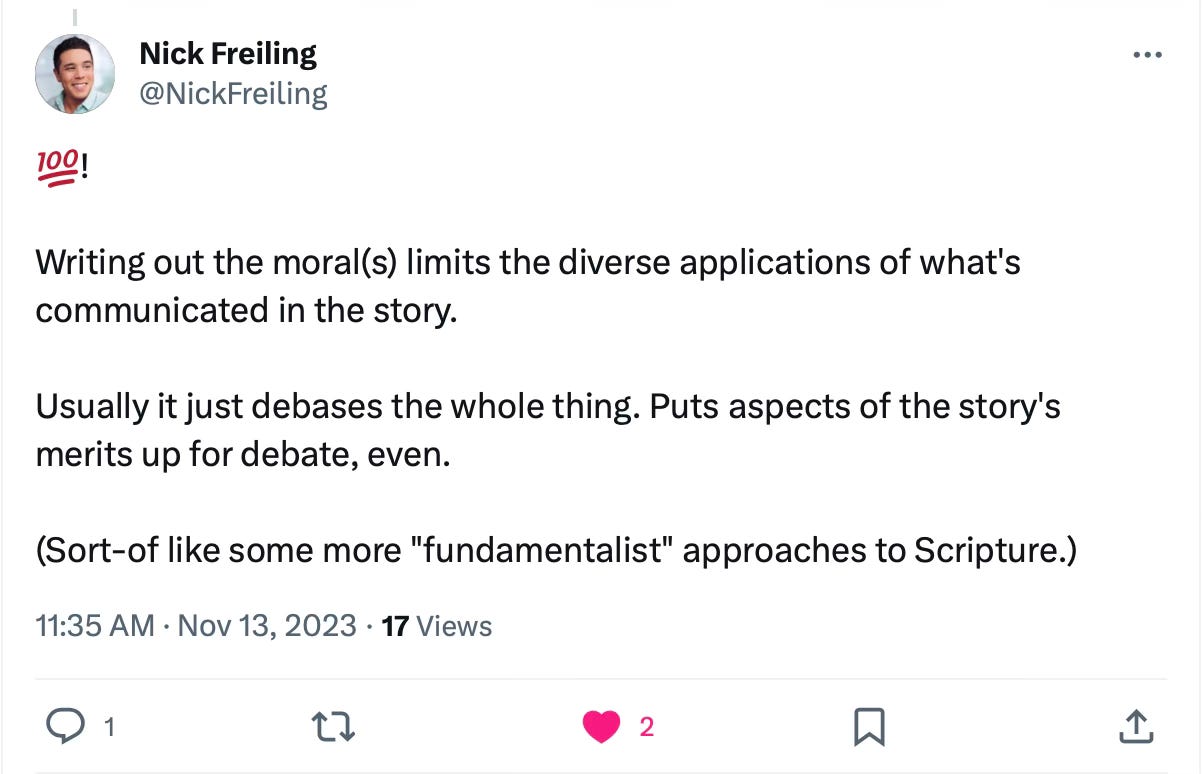

One person, Nick Freiling, put it like this on Twitter/X, recently:

He makes such a good point. The moral distracts us precisely by replacing all of the simplicity and beauty of the story with an aspect of the story that is now up for debate.

If we want to cultivate wisdom and virtue, we need to allow it to enter our souls in the way it is intended. No person will ever love courage because of a dictionary definition of it, but many will love courage because they want to be like the dog that embodies it. Or, to put a finer and more recognizable point on it, no one will ever love friendship because of a dictionary definition, but many will love friendship because they want to be like Samwise Gamgee, the great embodier of true friendship in all of the twentieth century literature.

Aesop’s Fables teach us to love virtues and despise vices not because they have excellent morals attached to them, but because they simply and beautifully embody those virtues in ways we can remember and even come to desire to imitate. The morals distract us from that embodiment and debase the simple beauty of the stories.

Read Aesop’s Fables. Read Aesop’s Fables to your children. But for the love of wisdom, leave off the morals.